University of Notre Dame sophomore Kelly Fallon’s eyes light up when she talks about her visit to Ditchling, the small village in East Sussex, England, where, in 1921, Eric Gill founded the Guild of St. Joseph and St. Dominic. The guild was a Roman Catholic community of artists and craftsmen, inspired by medieval guilds.

“I’d never heard of Gill before,” she says, “but going to Ditchling and seeing so many people who knew Gill and the guild really brought home to me how important he was to English art.”

Micahlyn Allen, a sophomore and Fallon’s classmate in professor John Sherman’s special studies course “The Guild of Saints Joseph and Dominic: An Early 20th Century Model of Faith, Work, and Social Activism,” agrees.

“It is easy to read about people in a book and ‘know’ where and how they lived, but until you have been there, it is a superficial knowledge,” she says. “Once you have walked the paths they took to their workshops every day and stood in their doorways, it is impossible to deny the humanity of these people.”

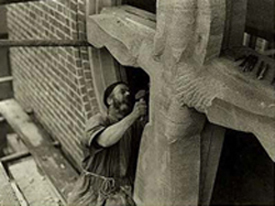

Gill (1882-1940) was an English engraver, sculptor, typographer and writer. He began his career at London’s Central School of Art where he studied with calligrapher Edward Johnston, who is famous for creating the London Underground typeface. Gill himself designed 11 typefaces; he is most famous for Perpetua and Gill Sans, both designed in the 1920s. From 1914 to 1918, Gill carved the Stations of the Cross in Westminster Cathedral. Gill came to Ditchling in 1919 in search of a lifestyle consistent with his beliefs about art, politics and society.

“As a political science major, I am very interested in the political and social theories in Gill’s writing and art,” says Juliana Hoffelder, a senior in Sherman’s class. Noting that Gill was an artistic provocateur, she says that she didn’t always agree with his message but that talking face-to-face with people who were members of the guild and scholars of the movement helped her appreciate Gill’s work. “They were excited to answer my questions, really happy to share what they knew about Gill,” she says.

Sherman, an associate professional specialist in the Department of Art, Art History and Design, sees Gill as especially compelling for Notre Dame students because his artistic community was so like the University’s academic community.

“For Gill and Guild members, artistic creation was a form of prayer. They lived an integrated life between work, prayer and play,” Sherman says, adding that aspects of Gill’s public life were in fact compartmentalized from his private life, which was not without controversy.

Students in the class explored the University’s Eric Gill Collection, which includes more than 2,000 pieces of the artist’s work, encompassing everything from books, pamphlets, sketches and prints to greeting cards, calendars, wood blocks and photographs; it also includes works of other guild members such as Hilary Pepler and Philip Hagreen.

As a capstone to their experiences in Sherman’s class, Fallon, Hoffelder and Allen produced a catalog and exhibit of Gill’s work. The exhibit, titled “All Art Is Propaganda,” will be on view at the Hesburgh Library in the Special Collections Room through August 20, from 8 a.m. to 5 p.m., Monday through Friday.

The Institute for Scholarship in the Liberal Arts; Learning Beyond the Classroom Faculty Lead Program; the Nanovic Institute for European Studies; the Center for Undergraduate Scholarly Engagement; and the Department of Art, Art History and Design all helped fund the project. Assistance also was provided by the staffs of the Victoria and Albert Museum, the British Museum and the Ditchling Museum.